When my mother, actress Fay Wray of King Kong fame, was a little girl growing up in the rough-and-tumble mining town of Lark, Utah, she could not have imagined one day she would come to Hollywood and star in one of the most enduring films of cinema history. Although most people remember her best for her adventures with the giant gorilla of Skull Island, she made over one hundred films during her career; in one two-year period, 1933-1934, she starred in twenty films, including Kong. It was the height of the Great Depression and she worked hard to support her family. She loved acting and hoped her movies might bring a moment of happiness to audiences in a distressed country where twenty-five percent of the people were unemployed.

In writing about my mother, whose life was extraordinary and at times improbable, I combed through photographs of her from the era. I was astounded by the beauty of some of the images. She had lovely features to be sure, but studio photographers had transformed her from an innocent young girl to one of Hollywood’s most striking women, just as they did for many of the men and women in the movies. There were hundreds of men – rarely women – who made their livelihoods taking publicity portraits and movie stills and were the unsung heroes of the motion picture business. Working only in black-and-white, they developed techniques that created what we still think of as the magic or “star quality” that made Hollywood actresses – Carole Lombard, Bette Davis, Loretta Young, Barbara Stanwyck, Greta Garbo— the envy of the world. Their sophisticated portraits were a departure from the soft and dreamy images of the 1910s and 1920s.

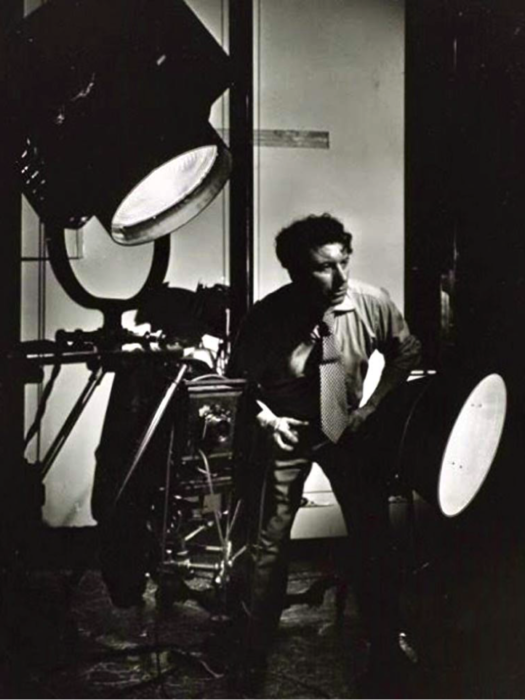

George Hurrell, largely unknown today except among Hollywood history lovers, was the first among equals and a star in his own right. According to Mark A. Vieira, who has written extensively about the photography of the era, it was Hurrell who pioneered the Hollywood glamour portrait of what grew to be known as the Hurrell style.

His approach was inventive and iconoclastic. He abandoned the soft lenses and filters used by his contemporaries, aiming instead for an intensity, clarity and sharpness. He used minimal lighting and strategic spotlights to create highlights or shadows to sculpt the face and give mood, feeling and drama. He seduced with light and shadow. In his hands, female stars of the 1930s became elegant, mysterious, even imperious. He sought an honesty in expression that came from inside his subject. For Hurrell, glamour began with personality within, which he worked hard to capture. “I would stand on my head, fall on my face, do anything just to keep things from looking like they were getting dull or that the excitement was falling apart.” He played romantic jazz recordings during his sessions to set the pace and mood of a shoot that might last four hours. A hard-driven, bigger than life character himself, Hurrell was “brilliant, mysterious, and mythic,” according to Vieira, and like many artists, had his own highs and lows. However, the results were uncontested. He was known as the Rembrandt of Hollywood.

I wondered how, without the modern tools for digital retouching, Hurrell and others from that era had produced images of women’s faces that were so flawless. I visited Vieira, in his studio where Hurrell once worked in the Granada Building in the heart of Hollywood, to ask him. His workspace was a reminder of a time gone by –softly lit, vintage equipment, 1930s jazz music playing. Black and white photographs covered the walls. Bookcases were filled with 16 mm prints of familiar movies. It was a temple to old Hollywood.

As we talked, Vieira spoke reverentially of the photographers of the era. “They didn’t think of themselves as artists – that would have been sissy – they thought they were just doing their job, but what they were doing was extraordinary.” He told me women didn’t wear base make-up when Hurrell shot them which surprised me. I assumed an actress would be fully made-up before a session to mask imperfections, but it was a retouch artist or Hurrell himself who applied a pencil lead directly onto the negative, making tiny strokes, little figure-eights, working painstakingly for hours to erase flaws and enhance contours until he achieved perfection. With an etching tool, he scraped on the negative to let light come through for a translucence. Without question, Hurrell was an artist.

I have selected some of my favorite photographs that Hurrell took of my mother in which he captures her beauty, kindness, intelligence and innocent sensuality. I plan to frame them for my wall to remember to her and that magical, timeless period in Hollywood history I still love.

2 thoughts on “Fay Wray, Hollywood Glamour and the Magic of George Hurrell”

It is certainly great to read about the enormous talent of George Hurrell. Many writers are quick to describe these wonderful images as glamorous and iconographic but we should not forget the artist behind the camera. Your mother, Fay Wray, certainly looked glamorous, iconographic and beautiful in these photographs but she was also enormously talented and kind. Thank you for sharing this very interesting information about your lovely mum but also for reminding everybody about the unique qualities of George Hurrell.

So well written!